JavaScript

Today, we learn the basics of JavaScript, and start by making simple programs that animate simple things with it. By the end of the next lecture (and a good amount of experimenting of your own), you will have most of the tools you need to write visualizations in JavaScript. Later in the course, we’ll use d3 because of its power and expressivity. But all that d3 does is create a powerful way to manipulate the underlying APIs we’ll be learning; it is important that you understand how d3 works.

Resources and reading

There are many good resources for learning JavaScript on the web.

As I did last week, I highly recommend Scott Murray’s “Interactive Data Visualization for the Web”, and specifically its chapter 3. And, again as I did last week, I’ll say you should just buy it if you can.

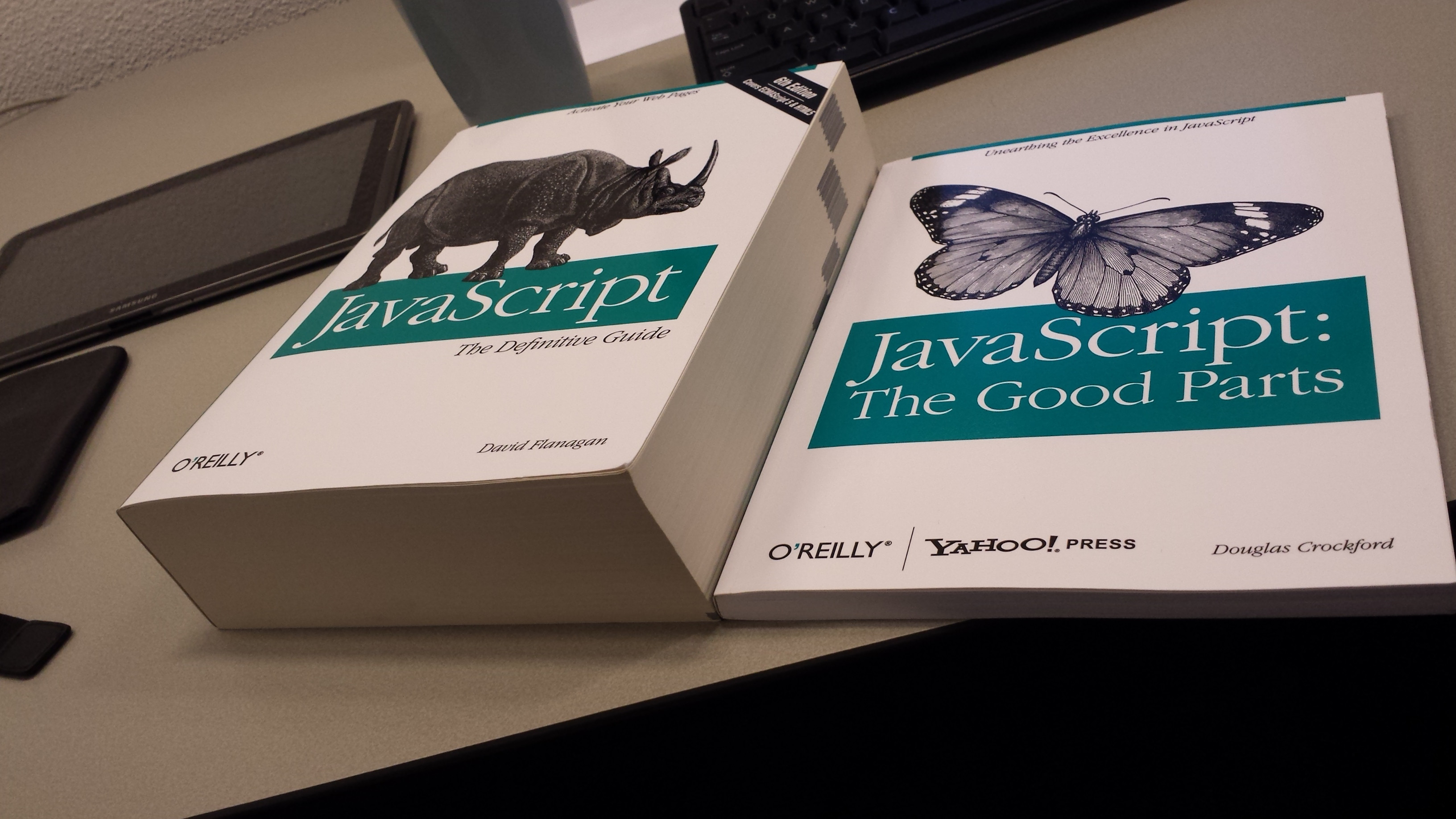

Douglas Crockford’s JavaScript, the Good Parts is at the time of writing also only 20 dollars, and it’s a handy reference.

Credit: /u/LethalSheep

Credit: /u/LethalSheep

David Herman’s Effective JavaScript is a bit more expensive, but also deeper.

In addition, you can also read the

Mozilla Developer Network’s JavaScript Guide. It

will cover much of what this covers. For a slower, more interactive

take on the same material, there’s

codecademy’s intro course.

Every time I search for javascript documentation on google, I just

throw in the term mdn, for Mozilla Developer Network. This makes

sure that MDN is in the first few hits, and the quality of the results

is much improved.

If you’re following the text below, my suggestion is that you either open the Developer Tools’s JavaScript console on a browser window, and type the examples to see what they do, like we go over in class. You should also try variants, and just generally play around with the console, to get a feel for the language.

Before we get started, though, a few words of warning: there is a lot of bad JavaScript advice on the internet. For example, although StackOverflow is typically a high-quality Q&A website, I would stay well away from it when it comes to JavaScript (why that is the case is beyond my understanding). Finally, the introduction below is not meant to give you a comprehensive description of JavaScript, but rather a foothold.

Once you become proficient in the language, then you can start worrying about best practices and special cases, especially as they related to performance and portability across browsers. It’s easier for you simply not to worry about that kind of stuff right now. This does mean that if you’re a veteran JavaScript programmer, you’ll spot places where what I’m writing is not 100% accurate. If you were to complain, you’d be technically correct, but what are you doing reading a JavaScript beginner’s guide? We’re in Tucson; it’s sunny outside!

JavaScript, the very basics

If you know any other mainstream programming language, JavaScript will feel sufficiently familiar. It has variables which hold values:

a = 0;

b = "1";

c = [1, 2, "3", [4]];

f = false;

f = 34.56;

The first thing to notice is that JavaScript’s variables are dynamically typed: you don’t need to declare their types before using them, and they can refer to values of different types at different times in the program execution. (This is convenient but quite error-prone: it’s usually a bad idea to make too much use of this feature.)

You also do not need to declare a variable ahead of time. If you don’t, then JavaScript either assumes you’re referring to an already existing variable, or it creates a new global variable. Again, this is convenient but very error-prone (this is a theme, as you’ll see). One common source of confusion is that typos in variable assignments are not caught: they just become global variables.

To create a local variable, use the keyword var:

var x = 0;

To print a value on the console, use console.log:

console.log(a);

console.log(22 / 7);

console.log(Math.PI);

Compound values in JavaScript will be of either of two types: arrays or objects. Array literals are declared using square brackets:

var c = [0,1,2];

var e = []; // empty array declaration

Arrays are addressed using square brackets, like many other languages:

console.log(c[0]);

(Notice that array values can have different types as well.) The other main type of compound value in JavaScript is the object. Objects are declared with curly brackets:

obj = {

key1: 3,

key2: 4

};

Array values be accessed with curly brackets, and so can object values:

console.log(obj["key1"]);

Notice how we’re using strings here as keys. Alternatively, you can use a familiar notation from other object-oriented languages:

console.log(obj.key1);

You can also add new fields to objects.

obj.key3 = "new value";

But, as usual, this can be error-prone:

obj.Key3 = "something"; // this is likely not what you meant!

These are the basics to get you started reading JavaScript code. We’ll say more about these values as needed.

Making more complicated programs

Programs that are just sequences of variable assignments are not very

exciting, and one way we usually build more complex programs is via

procedural abstraction. We define a sequence of steps we’d like to

give a special name, and create a procedure that performs those steps

for us. In JavaScript we use the keyword function for this:

function someFunction(v) {

if (v < 10) {

return v;

} else {

return v*v;

}

}

This produces the expected results:

console.log(someFunction(30));

console.log(someFunction(-5));

But, as usual, JavaScript lets you do strange things that are convenient sometimes, and confusing at other times:

console.log(someFunction("50"));

console.log(someFunction("what?"));

console.log(someFunction(30, "huh?"));

console.log(someFunction(30, "huh?"));

console.log(someFunction());

None of the calls above cause runtime errors. If you call a function

with too many parameters, JavaScript will simply ignore the extra

ones. If you call a function with too few parameters, JavaScript

gives the local parameters the special value undefined. Local

scopes (where local variables can be defined) can only be created

inside functions:

function anotherFunction(v2) {

var x = v2 * 10;

return x * v2;

}

console.log(x);

// If your global scope has no x variable, this will raise

// an error.

The typical way to declare a function to be called by a name is what we just saw. But there’s another important way to achieve the same effect:

someOtherFunction = function(v) {

if (v > 10) {

return "big";

} else {

return "small";

}

};

Pay attention to what’s happening here: this is assigning a value to a

variable, in the same way that x = "hi" assigns the string value

"hi" to the variable x. But that value is a function! This is

important. In JavaScript, functions are values that can be stored in

variables. When a variable is holding a function, you call that

function by using the parenthesis notation, as you’d expect:

someOtherFunction(30);

But later you can reassign that function, and then you’d be calling something else:

someOtherFunction = function(x) { return x - 5; };

someOtherFunction(30); // returns 25 instead of "big";

This is your first exposure to the idea that JavaScript is a “functional” language. In the same way that you can store function values in variables, you can pass them around as parameters, store them in arrays, object fields, and even use them as return values of other functions! This is a powerful idea that we will use a lot.

JavaScript has for loops, like C:

for (i=0; i<10; ++i) {

console.log(i);

}

While loops:

i = 3;

while (i<100) {

console.log(i);

i = i * 2;

}

Do loops:

i = 3;

do {

console.log(i);

i = i * 2;

} while (i<100);

and switch statements:

i = "some case";

switch (i) {

case "string literals ok":

console.log("Yes");

break;

case "some case":

console.log("Unlike C");

break;

}

Notice that the switch statement accepts string literals, unlike what you might be used to from C.

Making more complicated programs

If we create an object with slots that hold functions, this starts to look like methods from Java and Python. If we create a function that returns these objects, this starts to look like class contructors:

// Let's build something that looks like OOP

function createObject(content) {

var result = {

get: function() {

return content;

},

set: function(newValue) {

content = newValue;

},

twice: function() {

return content * 2;

}

};

return result;

}

f = createObject("something");

f.get();

f.twice();

f.set(20);

f.get();

f.twice();

It’s interesting to note how, with no class declarations, JavaScript provides something that has a strong “object-oriented” feel (in constrast to C++, Java, and Python). In fact, using just this pattern above, you can write a lot of object-oriented software. The only thing you’re missing is inheritance.

Inheritance, without classes

JavaScript does support a notion of inheritance, but it does it without any classes. This means that there’s no subclasses, so how does it work?

Instead of subclasses, JavaScript has the notion of a prototype

chain. Every JavaScript object has a special field which points to

another object. Then, every time you tell JavaScript to access a

field from an object, it tries to find the field. If the field exists,

then the lookup is performed. If, however, the field doesn’t exist,

then JavaScript checks for the presence of a special prototype field

in the object. If that field is not null, then the JavaScript

runtime performs a recursive access of the field in the prototype

object. This is more obvious with an example. Make sure to run these in

your JavaScript console:

// Inheritance, with no classes

base = {

v1: 1,

v2: 2

};

derived = {

v1: 5,

v3: 3,

v4: 4

};

console.log(base.v1);

console.log(derived.v1);

console.log(derived.v2);

// this calls sets the prototype of derived to be the base

Object.setPrototypeOf(derived, base);

console.log(derived.v1);

console.log(derived.v2);

This way, when you want to create a subclassing relationship, you do

it by defining a base object, and making sure that derived objects

have the base object as their prototypes. In practice, you would never

call setPrototypeOf directly. Instead, you’d call Object.create,

which creates a fresh new object without any fields (like {}), but

with a set prototype:

// Instead of using setPrototypeOf, use:

v = Object.create(null); // this is just the same as {}

v2 = Object.create(base);

v3 = Object.create(v2); // etc.

The special variable this

JavaScript has a special variable that is available at every scope

called this. When a function is called with a notation that

resembles methods in typical object-oriented languages, say

obj.method(), then this is bound to the object holding the method

(in this case obj). this allows you to make changes to the local

object:

function otherObject(value)

{

return {

x: value,

get: function() {

return this.x;

},

set: function(newValue) {

this.x = newValue;

}

};

}

Now try running these examples:

other = otherObject(3);

other.x;

other.get();

other.set(5);

other.get();

other.x; // compare example to "createObject"

So far, so good: we’ve used this to change the value bound to the

x field in the object from the object itself. That’s pretty

convenient.

However, the convenience comes with a caveat. The way JavaScript

decides to associate this with a given object is simple to explain,

but sometimes leads to strange behavior. The way it works is that

although obj.someFunction is the syntax to access the someFunction

slot from obj and someFunction(parameter) is the syntax to call a

the function value bound to someFunction with parameter parameter,

the syntax obj.someFunction(parameter) is not equivalent to

storing obj.someFunction to some temporary variable and calling

that. In other words, the syntax obj.someFunction(parameter)

consisting of those three things next to one another is special to

JavaScript.

Here’s what can go wrong:

function yetAnotherObject()

{

return {

x: 3,

get: function() { return this.x; };

};

}

obj = yetAnotherObject()

console.log(obj.get()); // fine

var t = obj.get;

console.log(t()); // *NOT* fine

What happened in the example that goes wrong is that when t() is

called, JavaScript doesn’t see the special notation

obj.method(params), and so it keeps the binding of this to its

present value.

Anytime you use this in a program and something goes wrong, the

first thing you should try to check is whether some call in your chain

forgot to set the binding by using the right syntax.

Functional programming in JavaScript

This is an important part of programming in JS that you might not be used to. Pay attention to this part.

In JavaScript, procedures are first-class citizens. What do we mean by that?

Consider a simple data type like a number. In other programming languages like C++ and Java, you can create a numeric constant, write expressions that manipulate numbers, assign a number to a variable, and return numbers as the results of a function call. Contrast this to what you can do with a procedure itself. You can define a procedure and bind it to a name; you can call a procedure, but you cannot1 return a new procedure as a return of a procedure call.

In JavaScript, you can do all of these and much more. Consider these two snippets of code:

function square(x)

{

return x * x;

}

var b = square(10);

var square = function(x)

{

return x * x;

}

var b = square(10);

They look almost identical, but pay attention to the syntax of the

second snippet: we’re defining a function value, and assigning it

to local variable square. This means that the second snippet is in

turn equivalent to this:

var b = (function(x) { return x * x; })(10);

That syntax is pretty goofy, and we’ll seldom have a reason to write code

like this directly, but it’s important that you understand why this works,

because a slightly different way to use functions is extremely common in

JavaScript (and in d3 especially). Consider this snippet:

function transformArray(f, theArray)

{

var result = [];

for (var i=0; i<theArray.length; ++i) {

var value = theArray[i];

result.push(f(value));

}

return result;

}

var numbers = [1,2,3,4];

console.log(transformArray(function(x) { return x * x; }, numbers));

Can you see what this snippet is doing? Now the function

transformArray does not need to know what its parameter f

does, and the code that calls transformArray does not need to give

that function a name: it can simply define it inline. This style of writing

code by defining a large number of small functions is extremely powerful,

and is ubiquitous in JavaScript. In fact, array objects have the following

methods: forEach, map, and filter. Experiment with these:

[1,2,3,4,5].forEach(function(x) { console.log(x); });

var squares = [1,2,3,4,5].map(function(x) { return x * x; });

squares.forEach(function(x) { console.log(x); });

[1,2,3,4,5].map(function(x) { return x * x; })

.filter(function(x) { return x % 2 === 1; })

.forEach(function(x) { console.log("Odd square: ", x); });

ES6 Fat Arrow functions

Modern browsers support a more recent version of JavaScript called “ES6”. We won’t use the vast majority of ES6 in class, but you might find it convenient to know that these are equivalent:

var square = function(x) { return x * x; }

var square = x => x * x;

var printAndSquare = function(x) {

console.log("Saw number", x);

return x * x;

}

var printAndSquare = x => {

console.log("Saw number", x);

return x * x;

}

Closures

The ability to return procedures as the result of another procedure call introduces a very powerful way to create abstractions. Consider this snippet:

function add(x) {

function f(y) {

return x + y;

}

return f;

}

var addFive = add(5);

var addTen = add(10);

console.log(addFive(1));

console.log(addTen(1));

The two instances of the inner f in add refer to two separate

values of x! The technical way to describe this phenomenon is that

f “closes over” x. , Since x is in the scope of f, each result

of add (f) is referring to a different value, and they remember each

separate value. This seems straightforward, but is extremely

powerful. Because functions play nice with the rest of JavaScript, you

can use these to encapsulate state (much like objects):

function makeCounter(initialValue) {

function bump() {

initialValue += 1;

return initialValue;

}

return bump;

}

var counter1 = makeCounter(0);

var counter2 = makeCounter(10);

console.log(counter1());

console.log(counter2());

console.log(counter2());

console.log(counter1());

Many JavaScript libraries (including d3) make extensive use of this

feature: we will study those cases as they come up, but you should be

aware of the existence of this technique.

DOM Manipulation

We have now seen all of the JavaScript we will need for this course. What we’re going to do now is start using JavaScript to change the DOM. Like we’ve seen in class, the HTML we write is represented as a tree inside the web browser. We now turn to the JavaScript APIs that web browsers provide to let you edit the DOM dynamically, so that we can build our visualizations with code instead of text editors.

Let’s get some boilerplate out of the way. (Note that the following

assumes that your document contains an element with id “hi”. If not,

you’ll have to create one such element first)

function radians(v) { return v * (Math.PI / 180); }

The method getElementById is used to return get an element from the

DOM (remember that an ‘element’ is simply a tree node):

mainDiv = document.getElementById("hi");

To add nodes to an existing node, use appendChild. To create text

content, use document.createTextNode:

mainDiv.appendChild(document.createTextNode("This is some text"));

With these, we can start to build software that creates more complex trees:

function divWithText(text) {

var result = document.createElement("div");

var textNode = document.createTextNode(text);

result.appendChild(textNode);

return result;

}

for (i=0; i<10; ++i) {

mainDiv.appendChild(divWithText(String(i*i)));

}

x = divWithText("X");

mainDiv.appendChild(x);

Sometimes, the appearance of an element is controlled by its

attributes (the things inside the opening tag; in <div id="foo"/>,

the attribute id has value foo:

function textAt(text, x, y) {

var node = divWithText(text);

node.setAttribute("style", "position:absolute; left: " + x + "px; top: " + y + "px;");

return node;

}

With this, we can place text at specific positions on the screen:

mainDiv.appendChild(textAt("hi", 20, 30));

for (i=0; i<360; i+=30) {

mainDiv.appendChild(textAt(

String(i),

100 + 100 * Math.cos(radians(i)),

100 + 100 * Math.sin(radians(i))));

}

Remember that in JavaScript we can attach new fields to existing objects. You can do this to DOM elements returned by the API, and that turns out to be very powerful:

function numberText(v) {

var node = divWithText(String(Math.floor(v)));

node.update = function(amount) {

v = v + amount;

node.textContent = String(Math.floor(v));

var x = 130 + 100 * Math.cos(radians(v));

var y = 130 + 100 * Math.sin(radians(v));

node.setAttribute("style", "position:absolute; left: " + x + "px; top: " + y + "px;");

};

node.update(0);

return node;

}

Note how in the above snippet, we are adding a new method update to

the node returned by divWithText. When this method is called, we use

add passed value to the current amount (stored at v), compute new

positions from v, and update the text content of the node.

With this function on hand, we can start working towards an animated demo. We begin by creating a list of nodes and storing them in an array.

var nodes = [];

for (i=0; i<360; i+=30) {

node = numberText(i);

mainDiv.appendChild(node);

nodes.push(node);

}

Then every time we want to move the nodes around the circle, we simply

call the update method:

for (i=0; i<nodes.length; ++i) {

nodes[i].update(10);

}

If we put this in a function, then all we need to do is call the function over and over again.

function tick() {

var i;

for (i=0; i<nodes.length; ++i) {

nodes[i].update(1);

}

}

We’re almost there. The main issue, now, is that we have to be careful not to send the web browser into an endless loop. For example, the following does not work:

// This will crash your browser (well, it'll send it looping

// forever until Chrome decides to kill the JavaScript process)

while (true) {

tick();

}

The reason for it is that although the element attributes are being

changed, the user of the web browser does not get to see it, because

the web browser does not ever get a chance to update the graphical

representation of the DOM. The way to solve this problem is by using a

special browser API called requestAnimationFrame. This API lets you

tell a web browser that you’d like the opportunity to change something

in the DOM. The next time the web browser is sitting idly,

after having drawn all of its needed graphics, it will call the

function passed as a parameter. Then, we just need to make sure that

after updating the graphics, we call requestAnimationFrame again. It

looks like this:

// this works!

function tickForever() {

tick();

window.requestAnimationFrame(tickForever);

}

This is very much like a recursive version of the endless loop above

(function f() { tick(); f(); }). The fundamental difference here is

that instead of making the recursive call directly, we ask the browser

to make the recursive call, after it has updated the graphics. This

way there’s always a step in between every update where the web

browser updates the UI and graphics, and you get nice animations as a

result.

-

If you know about inner classes and runnables and function pointers, you know this isn’t exactly accurate. If not, keep reading. ↩